Teaching physics is way different than teaching algebra, and I’m starting to get the hang of it. In both groups, there are diligent students and do-nothing students who have learned to slack their way thru with failing grades. In math, do-nothing students had more fun than diligent students, but diligent students have way more fun than do-nothing students in physics. When performing a lab activity like the index-card tower design, students may roll their eyes at first, but when the towers start going up and the excitement of competition sets in, even students who aren’t building are engaged with scouting other groups and speaking advice and encouragement. Engaging slackers is a constant battle in math, but they only need a poke to get started in physics.

It is said that “the key to classroom management is an engaging lesson” which I find easier to achieve in physics. Granted, the final unit this year is engineering, filled with authentic performance tasks, lots of hands-on activities, and no written exams (although I do include a few Kahoots as formative assessments).

Classes are bigger – and the difference between 39 and 23 students is huge! There is much more activity to watch, more students asking for help, more cell phones to confiscate, and one hall pass never seems to satisfy the need. I am left exhausted after 2 back-to-back periods and wonder how I would cope with 3 or 4 periods in a day.

I am struggling to fit in my TIP project. I intended to investigate the effect of 48-hour refresher tests on learning retention, but each class requires flexible response to student readiness, and the content and learning come first, so two experiment points have been skipped due to lack of time in the period. My data results are looking sketchy. I can hope it’s good enough for action research, but it wouldn’t cut the mustard in science or engineering circles.

Teaching

Assessment Re-re-visited

After a career in manufacturing, I am an expert in statistical sampling plans to monitor outgoing product quality. A random sample of each batch is split to be measured on separate test instruments and compared to experimental controls (historical golden units) to ensure consistency.

That’s not how schools do it. The third-party standardized tests (SAT, ACT, SBAC, OAKS) implement many (but not all) of those procedures, but normal classroom tests are crude approximations. The test condition varies, with students taking the test on different days & times, for different durations, in different rooms, with some taking the test in a pullout with a SPED teacher. Each teacher scores their own classes (not other classes) while interpreting the rubrics independently (if there is a rubric). Even if the test is unchanged from a prior year, samples of previous grading are not available.

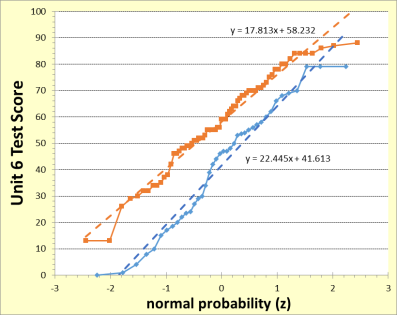

The result keeps us guessing why some teachers have better success. Did students learn more, or was grading more lenient? The graph below compares cumulative distributions of test scores from 3 periods of teacher A (in orange) and 2 periods of teacher B (in blue). Period-to-period differences are small for a given teacher. Note the huge difference between teachers, and the horrible success rate! Score<60 is failing, so only 46%/23% of students passed the unit test for teacher A/B, respectively.

So what is the result of this farrago? Many students go home to suffer “the lecture” from disappointed parents, and teacher B is pressured by school administrators to improve up to “the standard” set by teacher A. (As if a >50% failure rate were an acceptable standard.) Both teachers must go back and reteach the content. But what do we actually know for certain? NOTHING! This biased, uncontrolled experiment would be rejected for publication by any respectable journal. An unscrupulous player might use this graph to support any claim they care to make, and the flaws in data collection prevent us from countering their arguments. Garbage-in, garbage-out.

On the other hand, the spread in scores allows precise statistical analysis. The entire ‘bell curve’ of the population distribution is visible and available for analysis. If most of the students achieved 100%, then the distribution would be clipped (truncated), and censored data prevents measuring the student-to-student variation. We would see black & white, rather than shades of grey. It’s good that the test provides visibility. If we intend to categorize students into “emerging, proficient, and advanced” then we would devise the test with easy, medium, and challenge questions. We should not expect a barely proficient student to correctly answer the challenge questions, so what is a passing score? The criteria of awarding A/B/C/D for 90/80/70/60% correct is arbitrary with no statistical basis.

So what is a passing grade? Manufacturers look to customer requirements. (What quality level are they willing to pay for?) If teachers produce scholars, who is the customer and what quality do they demand? Students graduate and become butchers, bakers, and candlestick makers – each with very different quality requirements.

So how should we grade? Photocopies of identical tests, including “golden” tests graded in prior years, should be graded by multiple teachers and the results used to normalize the rubrics. Teachers should cross-pollinate, and swap a portion of tests to grade each other’s classes. Someone should look at the data.

Pedagogy Quality Control

How is it going?

In class today, I heard my peers gush about how they love teaching. Not to depress anyone’s mood, but is it OK to say that I don’t love teaching?

I love youth. I enjoy their energy and enthusiasm. I relish the company of inquiring minds. I want to be involved and help each of them to reach their own personal goals. However, I am reluctant to shove the curriculum down their throats.

I see my job as quality control of the information pipeline from the Common Core standards thru the textbook, and around the practice assignments and written assessments. Every step on the way has major flaws. The standards read like they were written by committee, with the pet projects of a few contributors interspersed with major compromises. The textbook was edited by compliant lackeys who included whatever the standard called for, so if (for example) the standard said to prove something, they included the driest most unmemorable proof possible. (I have elsewhere ranted that mathematical proofs are not productive pedagogy.) The only purpose for several pages of text was to check an item off their list. The problem sets can be ‘pure’ derivations without physical units and removed from context, or ludicrous word problems that distort physical reality to suit their ends. If a student asks when they would ever use this, I don’t have a good answer, because in a 30 year career I never did.

So do I enjoy it? Yes, on the whole I do. But I must endure repeated frustrations to relish the moments of bliss.

Adversarial Justice

When people don’t agree, a third person decides for them, and nobody gets what they want. In our judicial branch, the parties are identified as petitioner/respondent (civil), wife/husband (divorce), or prosecutor/defendant (criminal). Going to court means that negotiation/mediation/plea-bargaining has failed. In every case, no party gets what they want. (Even the judge or jury don’t get to choose as they like.)

I just wish my students knew that and would negotiate wisely.

In mathematical context, this can be modeled in several forms of game theory, but the basic rule is simple: “Never go to court unless the other party has something to lose.” If the court decision will be better, why would anyone accept the other party’s offer? It’s all about the art of the deal.

The teacher wants the student to stay on task and the student wants to dither. The usual smartphone distraction is bad, but is limited to an individual student. A chatty social butterfly distracts themselves and other students who could otherwise stay on task. When I intervened to get a pair refocused on the assignment this week, a student refused and responded that my interruption showed a lack of respect. Wow! Respect goes both ways, and if you don’t respect me then I have no obligation to respect you. So I wrote the referral to the dean of students, and she got detention.

Fair enough – if you expect to take break during math time, then I expect you to do math during break time. What did she expect would happen? Could she make some concession to my needs? I can accept a promise to refocus with a request for 2 minutes to wrap up. Instead, her final offer was something like “Go away and stop bothering us.” (I’m paraphrasing.) I was confident the administration would give me a better deal than that, so I declined her offer and went to court. Neither of us got what we wanted. (See above.) I’ll try to talk about strategies for her to get what she wants.

Student Teaching 101

I’m now 3 weeks into my practicum where I teach math classes for the slower students. My high school placement segregates students into ‘tracks’, so that students who successfully pass the Smarter Balance (SBAC) test in middle school will complete Algebra 2 as juniors. This would allow seniors to take an advanced elective like statistics or calculus (or nothing). Normal classes are scheduled on alternate days (A or B), but students who fail the SBAC are placed in Everyday Algebra which uses 2 class periods to meet daily. Thus, the slower group uses 5 credits to complete Algebra 2, compared to 3 credits for the faster track. What else could they have done with those 2 credits? They may have given up exploration of culinary arts, wood shop, world language, literature, or many options for a liberal education. Instead they hunker down and suffer thru my lessons.

|

Grade |

pass SBAC |

below standard |

|

9 |

Algebra |

Everyday Algebra (2 credits) |

|

10 |

Geometry |

Principles of Algebra & Geometry (PRAG) |

|

11 |

Algebra 2 |

Transition Algebra 2 |

|

12 |

Advanced Math Elective |

Algebra 2 |

And they do suffer. Of course, I do my best to break up the 90-minute class into varied activities and involve social learning as much as possible. But when I tell the class to “discuss with your elbow partner” the result is silence. Drat! After changing seat assignments to break up partners that distract each other, I’m left with table mates lacking any common connection and no desire to talk. When I assign an authentic performance task to groups of 4 (pairs-pair), I roam around to observe and help teams – only to have other teams go off task. (Thursday, students acted up, left their desks and were throwing foam balls and crumpled paper. There is still much middle school in my high school freshmen.)

So, as I develop my classroom management skills, and teach students responsible work habits, I dangle the carrot that learning is more fun when everyone acts mature. Meanwhile, keeping the whole class together in a discussion allows me to monitor everyone and maintain control – but it stinks too much of lecturing.

Humans evolved in a very different biological niche. Youthful enthusiasm and energy are great advantages in an agricultural society with chores to be done. They are a huge disadvantage in a modern (factory-model) classroom where they must sit still, be quiet, and take notes. Everyone can learn, and my students are clever, but I suspect their behavior is the reason they were categorized in the slower track. (I daydream of methods to teach math in the gymnasium.)

I am not yet “flying solo” in my classes. I file the flight plan, take off, and fly to the destination but I need help landing. The students watch the clock and go off-task, packing up with 10 minutes to go. I have arranged for my cooperating teacher to be away for most of the period but show up in the last few minutes to assist with crowd control. (I noticed during observation that even he had difficulty at the end of the last period on Fridays.)

I need to be better. I remember the students’ names but sometimes mess up the pronunciation. I plan good lessons but class discussions & check for understanding sometimes derail the schedule. I set lofty goals only to disappoint myself when I fall short. I’m not the best teacher, but that’s OK – I’m from Lake Wobegone where all the teachers are above average.

What the heck have I gotten myself into?

My teacher-prep MAT program has reached the end of Fall term, marking the half-way point. I am in a news blackout, where I can’t yet see Fall grades or Spring textbooks. Mid-winter break is a good time to take stock and reflect.

A course load of 20 credits was certainly too much. I expected about 3 hours/week/credit based on 2 hours of homework for every 1 hour of class, suggesting a 60-hour workweek – which I did for years working in industry. Not even close. The student-teaching practicum was 8 hr/w/c, and most classes were about 4, so I put in about 80-hours a week for many weeks. On the job, if I did 80 hours one week, I took comp time and worked 30 hours the next week. I am exhausted.

Am I slow? I am a slow writer. While I type at 80 words/minute, I delete about 79 words/minute. In a way, I stutter more while writing than when speaking – it just isn’t evident in the final copy. In previous technology coursework, I did the homework problems and sat for the final exam (more problems). In liberal arts classes, I’m expected to complete ‘products’ – which invariably involve a lot of writing. (While pedagogy tells teachers to provide students with multiple ways to show proficiency, both tech and education courses are single-minded, each in their own way.)

With school, teaching, and family demands, the only give in my schedule is sleep time. My wife has heard me say that “I can drive truck after 4 hours sleep, balance the checkbook after 6, solve brain-teasers after 8, and write poetry after 10.” The teacher-prep program taxes the creative/linguistic parts of my brain that simply do not function when I am sleep-deprived. My weekly task list becomes a death spiral as I put in more hours which makes additional hours less productive. My work quality suffers and my frustration grows until I pass the deadline and must submit substandard work in order to begin the next assignment.

At all times I am careful about mental health. Fall is my favorite season – from Minnesota Indian summers in my youth with sunny “sweater weather” afternoons after the first frost has killed the mosquitoes. Regardless of preference, I am subject to seasonal affective disorder (SAD), which I control with lunchtime daylight walks. Oregon doesn’t always provide sunshine, and November can have long periods of rain, during which “disorder” is too mild a term and my cognitive function borders on depression. My brother takes Wellbutrin 3 months each year to combat his SAD, and perhaps I should go the pharmaceutical route also. The longest, rainiest January is no problem because I’m over it by then.

When I flew airplanes, I used takeoff and landing checklists to avoid forgetting anything. Likewise, I have a draft of my pre- and post- lesson checklists to make ensure all the bases are covered. My daughters were coached to turn their heads when checking traffic during their driving test, because the examiner can’t see their eyeballs scan. Likewise, pedagogy teachers insist on lesson plans to make sure the student includes all the necessities – even though employed teachers rarely make them or use them. We are supposed to anticipate student difficulties and differentiate instruction, but in real life I have a TAG/SPED/EL student who would be insulted by any instruction I might provide to a “slower” student. I don’t have generic exceptions – I have individual exceptions with unique personalities. Good public speakers do not read a script, and the best classroom discussions and inquiry flow extemporaneously. There should be a pedagogy course on improv – but of course I would need 10 hours sleep for that.

So, what does the future entail? January term looks to be 80 hours/week for 3-weeks, and if I survive that, it’s followed by 18 weeks of maybe 50 hours/week. And I may be bored all summer. [As I re-read the above, I’m thinking “what a whiner – wah, wah, wah!” I will pull up my big boy panties and deal with it.]

Khan Academy Online Math Resources

Salman Khan has done a fantastic job integrating educational math resources, but as an engineer and STEM educator I cringe at some of the models used in the problems. A video on quadratic equations (somewhat out of order in my opinion) shows an equation in factored form which predicts mosquito population in New York (in millions), m=-r(r-4), where r is rainfall in cm. The two zeros predict zero mosquitoes at 0 cm (drought) and 4 cm (flood) – but annual rainfall in New York is 114 cm – far more than 4cm – and doesn’t wash away the mosquitoes. The narrator at 2:51 is out of touch with reality – but maybe he means 4 meters, not 4 centimeters.

Khan Academy is an excellent resource for pure math learning, but I think most middle-high school students find that irrelevant. I believe that students need science to make sense of math and they need math to make sense of science, and the connection must be sensible and logical. My job as an educator is to review video content and be ready to remediate any confusing or illogical content. Salman Khan has acknowledged their limitations: “I think they’re valuable, but I’d never say they somehow constitute a complete education.”

Thoughts on the Flipped Classroom

Let’s say we have two choices:

- Sit thru a lecture by a ‘sage on the stage’ during class with no opportunity to check for understanding (CFU), and then do practice problems at home (homework) with no resources available (neither teacher nor classmates) to clarify questions.

- Watch a video presentation at home explaining the concepts and then work sample problems in class with others to ask & compare work while the teacher checks progress.

If #1 is the traditional classroom model, then #2 is the new much-touted ‘flipped’ classroom. If these were the only choices, I can see great benefits to the second model – but we are not constrained to that either/or choice. Options include

- Remote learning, where the student independently learns concepts and practices proficiency at his/her own pace

- The double-class model (such as the every-day Algebra class that I will teach) which replaces homework with an additional elective credit class period in school

- And everything in between

The completion rate of open on-line courses (MOOC) is very low, so it takes an unusually motivated student to accomplish #3. Districts that attempt #4 have a hit-or-miss track record depending on what strategies they use in the math support class. (Perhaps the best strategy is to stop spoon-feeding struggling students and teach them how to advocate for themselves.)

My discussions with practicing teachers reveal challenges to implementing the flipped classroom. We are teaching perseverance, which is hampered if they give up after 2 seconds to ask their elbow partner (or just copy the answer). The students who most need the content lesson are the ones least likely to watch it on their own, requiring greater effort by the teacher to differentiate instruction. The social benefit to learning is optimized in class discussion with participation by all students, which is lacking while passively viewing a video. So the best learning model is:

- Class time that is well organized and structured around worthy tasks, followed by intelligent homework

‘Relay’ is a classroom activity where pairs work problems together, one as solver and the other as coach. The teacher matched them up carefully, and selects problems for them to work on – either skipping ahead to harder tasks or holding them back to repeat simpler tasks. Homework should be like that. Instead of assigning “problems 1 to 20 on page 345”, a teacher could assign a flow chart, like “Start with problem n (selected per student) and if your answer is correct skip the next 2 problems and work the 3rd problem. Continue until you accomplish 10 problems correctly. If 3 problems in a row are incorrect, then stop and advocate for yourself by finding and getting 10 minutes of one-on-one tutoring outside of class.” Flipped classroom videos are a valuable resource, and should be part of the homework flow chart: “If problem #6 is incorrect, watch this video and write a sentence to describe what you learned.”

A teacher must respect their students time and not assign busywork or frustrate students into beating their head on the wall. Students must practice diligence, develop endurance, and own their education.

How to Lie with Statistics

Many good books were published in 1954 including some about the Lord of the Ring (#1), Sherlock Holmes (#14), James Bond (#17), and statistics (#22).

Here is a subject near and dear to my heart. Back in high school I considered a career as an actuary, started as a math major in college, switched to a technical field, and worked as a reliability engineer (which is like an actuary of manufactured goods). Statistics was my bread and butter for many years.

Darrell Huff collected anecdotes from colleagues at the American Statistical Association and included them with fun images in a book to debunk the distortions foisted on the public by those with an agenda. He doesn’t distinguish fraud from incompetence, but “When all the mistakes are in the cashier’s favor, you can’t help wondering.” (p.71)

Sample plans usually impose a bias because better plans are way too expensive. The data can’t be trusted, especially when respondents are self-reporting. Mean, median, and mode are alternately selected to best inflate the evidence presented. If you measure the dependency of 100 totally unrelated variables to 95% confidence, you are likely to find that 5 of them are statistically significant. (If you ran the experiment again it would be a different 5.) Line graphs that omit the origin and bar charts that use 3-dimensional figures are likely to exaggerate small effects. “A difference is a difference only if it makes a difference.” (p.58) If clock A strikes when clock B points to the hour is there cause and effect? Reporting 4 significant digits despite ±10% accuracy is just stupid. Also misleading is reporting 33% instead of “one out of 3”. Proportions are tricky because after a 50% reduction it takes a 100% increase to return to the basis. Words can hide the truth as effectively as statistics, and the author gives examples of wordplay, comparing “light and economical” to “flimsy and cheap”, and presenting a medicine that promises “quick ephemeral relief”.

Chapter 10 proposes defenses against bad data. This reads like later skeptics, such as Carl Sagan’s Baloney Detection Kit. As a STEM teacher (math & physics) I am committed to educating everyone to become prudent consumers of products, including data and media information. This may stray into philosophy when I present Occam’s razor and the maxim “A wise man … proportions his belief to the evidence.” (Hume) I am amazed that some who were taken in by a scam leave themselves vulnerable to a repeat. Teachers must enable higher cognitive levels in their students to look past the surface features and understand the deeper meaning in what they see. I would see it as a positive sign if my students challenge me for proof of what I say.

5 Practices, Chapters 7-8

Thoughtful and thorough lesson planning is essential for my success. I have been asked to teach a lesson after walking in cold and it was a painful and nerve-wracking ordeal. Even the straight-forward task of working exercises in the text left me apologizing for typographic errors on the page, and glancing ahead to determine where we were going. The Thinking Through a Lesson Protocol (TTLP) from Smith, Bill, and Hughes seems a good overview and checklist of what to include. By starting with the learning goals and selecting a suitable mathematical task, the flow of the lesson and assessment unwinds itself. I especially liked the question “what will you do tomorrow to build on this?” In comparison, other lesson plan templates given in various MAT classes are the type of fill-in-the-blank worksheet for teachers that we abhor for students. I hope to be more like Keith than Paige.

I am still struggling with top-down lesson planning. If you tell me what to teach, I can match it to the state standards and present it in a sophisticated way that will engage students. My difficulty is in creating a calendar of a learning unit and breaking it into bite-size pieces that fit into an 89-minute block. I suppose it will come with practice once I have cut a lesson short after running out of time and another time added filler when I ran out of content. At my high school, the teachers for different sections of the same course cooperate to align their content and synchronize the exams, so in practice I may rely on the experience of the team to optimize the amount of lesson content.

The example of Maria is presented to show that continuous improvement is possible and desirable. (I understand perfectly as I come from industry where Six-Sigma, Lean, TQM and other continuous improvement programs are mandatory.) She managed to organize a quality improvement team and get her boss on board to investigate how to improve student outcomes. The authors lament the possibility that the “supervisor may not understand or support the approach” which gets me wondering if the authors have experienced a painful history of that very possibility…